Models of Leadership — “leader-leader”

Models of Leadership — “leader-leader”

This blog explores a recent book I read written by a retired US Navy Submarine Captain L. David Marquet entitled “Turn the Ship Around!”, and the leader-leader model of leadership he establishes and describes the implementation of into the USS Santa Fe SSN.

The Problem with “Leader-Follower”

Marquet starts by establishing the problem: the lack of ownership amongst his workforce. The reason, he attributes, is the leader-follower model of leadership shown within the Navy and within most organizations. The leader is in control, is accountable, and so leaders are encouraged to limit the decision-making authority of those who work for them. Employees have little incentive to innovate and find solutions that support the overall organizational goals. Traditional accountability structures also tie the performance of the organization to the performance of the leader, and vice versa, so that when leaders leave the organization is worse off.

He presents the implementation of a leader-leader structure — where his staff are truly empowered to make their own decisions and take responsibility for their divisions. This decouples the leader’s personality and presence from the performance of the organization as a whole, meaning that the improvements continue even after the leader moves on.

Control, Clarity, Competence

Marquet discusses the changes he made as CO of the Santa Fe, and splits these mechanisms into 3 categories: control, clarity, and competence.

His primary aim was to divest control by “moving the authority to the information”. However, if you divest control without improving clarity and competence alongside, you will not be able to make these changes. For example, if you let technicians prioritize their workload (control) but they don’t have enough technical knowledge (competence) or they don’t understand how their work fits in with the overall organization strategy (clarity) then the exercise will fail.

The rest of this review blog will introduce a couple of these mechanisms for each category, and give a summary of the example given in the book. There are many more mechanisms discussed in detail in the book, and I highly recommend you read it in full. Finally, I will discuss how these principles and mechanisms can be integrated into business organizations, particularly from my perspective in consultancy.

Principles of Control

FIND THE GENETIC CODE AND REWRITE IT

Each organization will have a structure for delegating control. Most initiatives for empowerment will work within this structure — i.e. changing the details of who exactly approves something, but ultimately flowing responsibility back up to the top. Any directed empowerment programme will ultimately fail — because by directing something to happen you are fundamentally disempowering those you intend to empower. Instead, Marquet believes that you have to fundamentally rewrite the power structures and authority delegation

Marquet gives an example of doing this. For an enlisted submariner to take leave, it had to be approved by everyone up to and including the executive officer (XO, second-in-command of the vessel). He fundamentally changed the genetic code of the authority structure by altering the regulations to make the final authority for enlisted personnel the chief of the boat (COB) — the senior enlisted submariner. This provides true divestment of control that actually empowers the COB to take responsibility for ensuring that there are enough enlisted submariners on board to fulfil the needs of the boat. This links to competence and clarity as well — competence is required to understand the amount of work required and to take on the additional administrative burden, and clarity is required to understand the boat’s operational requirements for staffing.

SHORT, EARLY CONVERSATIONS

Marquet summarizes the need for this mechanism in just three words: “perfect, but irrelevant”. No matter the effort, skill, or experience that has gone into the creation of some artifact, the relevance of that artifact towards that actual goal can drastically affect its usefulness towards the high-level goals. Short, early conversations that promote communication between all levels of the command hierarchy improve the relevance of work.

An example he gives is regarding colours used to annotate maps of operational deployment areas. The quartermasters simply used whatever colours happened to be available at the time — so the good deal of effort and time they took in colour-coding it accurately was negated by more senior officers having to look up the legend which was different each time. This is particularly relevant when the map may need to be referred to in the dark, and in high pressure, busy situations. By having a short conversation with them to explain the significance and importance of their work, which was early by not rigidly sticking to the structures of command, Marquet was able to significantly improve the utility of the maps with the goal of operational excellence.

I INTEND TO…

This is one of the most powerful tools, I believe, in the whole book. Marquet asked his officers to fundamentally change the way that they phrased requests to a superior to do something. By changing from “Requesting permission to … ”, he set out the “I intend to… ” framework. This eventually filtered down to all submariners as well. The significance of this is that it forces everyone to take accountability for the decision they are about to make — turning them from passive followers to active leaders. It shifts ownership to those executing the plan.

There are multiple phrases that exhibit this disempowerment: “Request permission to…”, “I would like to…”, “What should I do about…”, “Do you think we should…”. Conventional management wisdom encourages these phrases — saying that questioning and involvement improves decision making. But one fundamental issue is not addressed — the fact that, by using these phrases, one is still leaning on a superior as the decision-maker, the accountable authority, and as such they are fundamentally disempowered from making the decision. Contrast this with phrases such as: “I intend to…”, “I plan on…”, “I will…”, “We will…”, and the effect that this has on the stake that someone has in the decision.

It’s also important to note that the reasoning behind why someone wants to do something is also important. Marquet also details the second stage that he took with his officers and men — the “I intend to…” request should also contain enough extra detail about the reasoning and caveats to it that all it should require as a response is “Very well”.

Principles of Competence

TAKE DELIBERATE ACTION

Marquet starts this section by discussing a review of a major safety breach by a petty officer during an inspection. They discuss how it could be prevented and identified it was a “automatic mistake” — a mistake caused by operating on autopilot, and by default. They identified that following procedures blindly was a key cause of mistakes, and by carrying out tasks immediately, it prevents the correction of mistakes by any level of supervision. They instituted a policy of “take deliberate action” — before completing any action, operators began to pause, vocalize what they were about to do, then complete the action. This means that thought is necessary for every action, and also allows the appropriate time for dissent or intervention.

He also discusses the key problems with adoption of this approach: a sense that this is only being done for the sake of inspection (when in reality it is aimed to prevent any and all errors caused by default actions); and the sense that this is only to be used in day-to-day (peacetime) operations (when in reality, its worth comes to the fore in moments of pressure and when fast, accurate responses are required). Fundamentally this work aims to block error propagation and create a resilient organization.

DON’T BRIEF, CERTIFY

There is a strong military tradition of briefings. This is embedded into soldiers from Day 1 (quite literally, the formal kick-off of UK Army recruitment is an Army Brief Day). However, briefings are a passive process. Marquet documents a dive process exercise, where the Diving Officer of the Watch (DOOW) briefed as procedures states from the Ship System Manual (SSM). Things went wrong - the wrong actions were taken at the wrong time, with inadequate responses to errors. Rather than taking responsibility for their own understanding of the procedures, they relied on a verbal “information dump”. Additionally, a briefing should indicate a decision point — a point at which the operation is executed or not. A passive briefing is simply a discussion before the execution of the operation, and has little relevance towards the actual method used.

Marquet instead proposed the certification concept. At the decision point before commencing an operation, the leader of the team asks them questions about the procedure that is to be carried out. They form an assessment of the overall readiness of the team to complete the operation that is required of them. This forces responsibility for knowledge of the operation onto those who will be implementing it — giving them accountability for preparing their own knowledge. This changes behavior and attitudes towards active participation and intellectual involvement.

SPECIFY GOALS, NOT METHODS

This is a common message, but worth repeating. No amount of procedure or doctrine matters if the objective is not achieved. Marquet particularly emphasized the importance of this during emergency response, such as the response to a fire. The damage control officer sets the goals over the PA, and individual officers, teams, chiefs, and enlisted men make decisions about how best to achieve that objective. This decentralization speeds up decision making, improves the decisions made, and relieves the burden of issuing specific orders from senior leadership, so they can focus on the overall response.

Principles of Clarity

ACHIEVE EXCELLENCE, DON’T JUST AVOID ERRORS

Avoidance of errors is a noble pursuit. Errors cost money, time, lives, outcomes. But the avoidance of errors over all else creates a culture of risk-avoidance by inaction and creates a destiny of failure, as you can never remove all errors. Success will be benchmarked as a negative, an avoidance of failure — as Marquet states: “your success is no punishment”.

To achieve the clarity needed to embody excellence, the avoidance of errors must take a back-foot to the understanding of the source of the errors. This is a challenging mindset for many to adopt, especially in high-safety-pressure environments such as whenever there is nuclear involvement. Reduction in errors is obviously important, but excellence suffers if that is your only goal.

BUILD TRUST AND TAKE CARE OF YOUR PEOPLE

This principle is something that is fairly ubiquitous now — the idea that the better supported your staff are, the more effective they will be towards your organizational objectives. Marquet emphasizes two key points — not just asking your people to tick off certain academic or training requirements, but identifying what requirements actually matter in their lives and supporting them in this, and helping them take time for the personal lives despite work pressures.

Marquet gives two examples of this. Firstly, they conducted analysis on why many of their petty officers were not promoted by the Navy Advancement Board. They discovered that one exam component was the key differentiator between those who were promoted and who weren’t. To solve this, they didn’t just encourage their teams to study for it, they created internal advancement exams that echoed the content and style of the problematic exam, which drastically improved promotion rates in the next cycle. Secondly, he details how the resilient officer team he had built was able to cope with several senior officers on personal leave, despite operational pressures.

Finally he also emphasizes that “taking care of your people” doesn’t mean protecting them from consequences of their own behavior. It means giving them every opportunity to succeed and fulfil their ambitions.

BEGIN WITH THE END IN MIND

Marquet emphasizes throughout the book the need to have long-term thinking strategies, but sets out how this can be achieved here. He sets out 3 key activities to improve the thinking of an organization.

- Ensure that your leadership team make long-term strategic plans (3–5 years). This is particularly relevant in contract or time-limited work, even though the time pressure it seems to reduce in importance.

- Ensure that employee evaluations are written with measureable metrics. If you can’t measure your metrics, then you’re using the wrong metrics!

- Ask your employees to write their evaluations for 1, 2, or 3 years in the future, which gives a structure and a framework for them to work towards.

Discussion and Conclusions

IMPACT

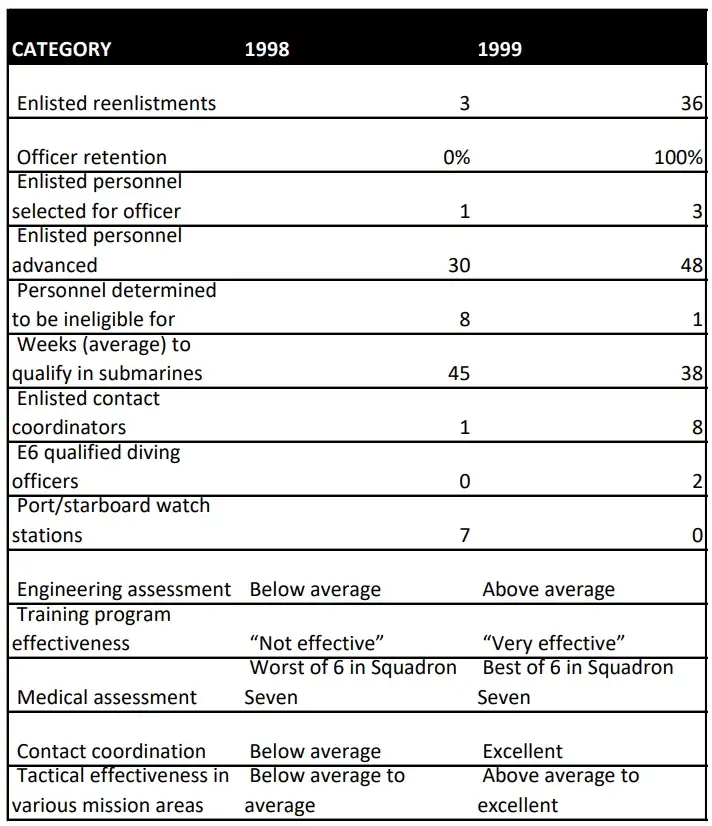

Marquet finally sets out the remarkable impact that these actions have had. The most important things is that these improvements were not around the success of himself as a Captain. His personnel were much more successful as well — particularly the increases in enlisted personnel advancement, and the shortened time to qualify in submarines. In addition, these improvements continued after he was no longer in command, due to the skills and attitude developed in everyone on board. For example, the submarine won the “Best E” award for the most combat-effective submarine in the squadron 3 times in the decade after he left.

The evidence is clear — the leader-leader approach builds powerful, effective leaders at every level of the hierarchy, builds resilient, effective organizations, and actually empowers employees.

IMPLEMENTATION

This is always the challenge about large changes to an organization — how do you actually decide, plan, resource, and deliver change in large, possibly remote, teams.

I think the important thing to recognize about the mechanisms that Marquet suggests is that they all support the implementation of each other. As you begin to divest control, it becomes easier and easier to make changes, as your empowered middle-grade leadership takes responsibility for enacting and monitoring changes, and less is driven from the top.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Invest in your people with time, development, support, and authority.

- Focus on cross-cutting communication, and common-sense outcome-focussed principles rather than layers of bureaucracy.

- Drive active involvement and reduce passivity.

Thanks for reading! Marquet’s book contains much more detail on all of these topics, and more mechanisms and guidance besides — so I would really recommend picking up a copy of “Turn the Ship Around!”. Let me know if you have any thoughts on any of the topic as discussion and criticism of my writing is very welcome!